I have the woodburner on.

I'm on holiday.

There is something deliciously satisfying about being indoors on a very wet autumnal day. It is just before noon and glimpsed through the window the rain is falling as only rain can in this part of Herefordshire. Sweeping over the Black Mountains in pulsating drifts from the west, often these bands of rain-bearing clouds run out of puff on reaching Herefordshire,their exhaustion sparing the the Golden Valley, such is the rain shadow effect of those brooding Welsh uplands. Not today. Hard after Storm Ali swept the northern extremities of these Isles of Britain, this sweeping dragon's tail of heavy rain thrashes in Ali's wake, providing opportunity for a self-imposed curfew. It is dark outside, and within too. The Old School House where we're staying in Bredwardine is bathed with an internal twilight - a mood enhanced by a robin which, since dawn, has been serenading the rainfall with its mellifluous song.

Yet, a mere 24 hours earlier we (Julie and I) followed in the trail of the Reverend Francis Kilvert. I have to confess that until recently whilst I had heard of Kilvert and his famous diary, my knowledge of him ended there. Staying in the hamlet of Bredwardine where he was incumbent of the living for only eighteen months, it is hard to escape the presence of this Wiltshire born man. The cottage has his three volume diary to read. Pamphlets and books add to the visitors' understanding of this long distance walking, scribbling vicar who died prematurely aged only 38 in 1879. Kilvert began his diary in 1870 whilst a journeyman curate in the village of Clyro in Wales. Remaining in Clyro for seven years the Oxford educated Kilvert arrived in Bredwardine in 1877 only to succumb to peritonitis, five weeks after his marriage. Kilvert's life reminded me of another chronicler of the rural ordinary, the Wiltshire born Richard Jefferies, who like Kilvert suffered from poor health in his latter years and died in 1887 also aged 38. Did their paths ever cross I wonder? That's for another day.

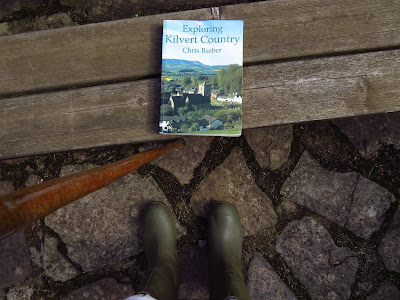

In the cottage was the book - Exploring Kilvert's Country, an interesting summary of the places and well described walks, affording an opportunity to learn more of this man. As the cottage was the schoolmaste'rs home in Victorian times, I am sure Kilvert would have visited here during his time. Thus given I'm in Kilvert's village, a 4 mile circular walk seemed perfect to glean a deeper understanding of the landscape Kilvert described as "...the lovely valley gleaming bright in the clear shining rain.......and the river blazed below the grey bridge with a sparkle of a million diamonds....." Wellies on, stick to the fore, book in hand...to the jewel of Herefordshire then...

First steps down the drive from the cottage and onto the road, bear left into the village - at the crossroads turn right and walk down towards the church...

On returning from his Honeymoon Kilvert and his wife were, (having unhitched the horses) pulled by the inhabitants of Bredwardine and Brobury to the vicarage and a celebratory feast. The vicarage is further down the hill, but this beech tree-lined walk up to the church is one Kilvert knew very well.

Entering St Andrew's churchyard the first thing to grab the visitor's attention is this memorial seat by a yew tree. Erected a few years ago by the Kilvert Society, it now has two 'legs' where previously it had been set atop a low stone wall. On a few websites this is referred to as Kilvert's 'Tomb' which is quite wrong; this may explain why the wall was removed and the legs were added. Bear right to enter the church, or left at this junction and meander up through the graves where a white cross dominates the northern end of the area. Here lieth Francis Kilvert, at a plot he himself picked out to be buried at. The two graves either side were close friends of Kilvert, the Misses Julia and Catherine Newton. So close are these graves that when Kilvert's widow died in 1911, despite visiting his grave every year after his death, she had to be buried some distance from her husband in the new cemetery on the south side of the church.

Today his grave is cared for and being of white marble, stands out in this very peaceful churchyard.

St Andrew's itself is Norman in origin and fascinating. It is the only church I've been in which is bent. Originally built just after the Norman Conquest in the eleventh century, sometime around 1300 it was extended but the chancel is strangely askew to the rest of the building. No one seems to know why. I like this diversion from the perpendicular. 700 years ago I can imagine stonemasons building away, before the foreman arrived and said "lads, lads lads, that's not straight" Did they all sit down and discuss what to do over a few beers? Before deciding, it was too much effort to knock it all down again, 'no one will notice', just keep turning left!

The church also has a good second hand bookstall, this being Hay-On-Wye country and I bought myself a slim volume on woodworking techniques with a router for a whole £1. I digress.

Back to the walk. Leaving St Andrew's the bridleway follows the southern perimeter of the churchyard and then descends slowly to follow the river Wye. Sadly though, while the river is ever present on the left, with the trees still in full leaf, it is almost impossible to see, though later in the walk it looms into view like a borderland serpent carving through the valley.

The well kept bridleway traversed by Mrs Wessex Reiver

Into the woods, which on a very windy day made for an exciting walk as small branches crashed down around us.

Medieval fishponds glimpsed through some of the many ancient oaks hereabouts.

Accompanied by locals ...

... before heading into wonderful rolling farmland with Merbach Hill in the distance. That was pounded up the day before, and as a climb of over 1000 feet to the summit, it really was a pounding walk.

This bit of the walk was easy to navigate. Later on it became more tricky to find where the footpath went to and from. The landscape will not have changed much since Kilvert strode out over the fields, glimpsing the river as it meanders and curves its way through this red sandstone area.

Kilvert though may have been surprised to walk through fields of maize and a pheasant-rearing facility. but then again, he may not - this has long been a proper rural landscape, red in tooth and claw..

Eventually reaching the half way mark, we turned southwest again to walk along a B road for a while, passing Moccas Park, an ancient park landscape which this photograph does not do justice to. I want to head out there one evening before leaving the cottage as I have an notion that the rooks and jackdaws which seem to pre-roost in Bredwardine, roost over in Moccas park. This would make sense as they are site specific for centuries.

After Moccas Park the walk took us up through the fields behind Bredwardine. Autumn fungi were everywhere on these un-ravaged sheep pastures. However despite following the very well described walk from the book which was published in 2003, for the last couple of miles the footpath network left a lot to be desired. And discussed, sometimes heatedly. We'd also left our water bottle in the church which didn't help quench the mood. Walking is meant to be relaxing, right? Many footpath signs were either missing or illegible, forcing us to backtrack more than once after finding ourselves in a no-mans-land oF indecision at a fence line or in a house driveway, which was a shame as the walk is absolutely lovely, and doing it again it would be easier as we would know where to aim for. I'm still not certain though walking through someone's garden at the end of the walk to get to Bredwardine was correct, so we climbed over a gate.

Across the sheep fields

Bredwardine church mid view

Dorstone Lane..... not for the faint hearted if driving a car... narrow, 1:4 hill with no passing places used by locals as a rat run and scene last years of some hair raising drives.

Half an hour from home the rains came, like the sheep in the fields, we took cover. Until the sun came out, and having lost the footpath again, just walked around the edge of a field.

Back in the village at last, where nature is taking over from window cleaners. I like that.

The End.

I was happy there, but following in the footsteps of Kilvert in 2018 was not an altogether pleasurable experience. The views and the connection to his landscape were breathtaking. Being lost even when following a guide and a map was less welcome. This happened to us last year in the other valley, where a footpath just stopped. Which is the lesson for the modern walker, following in the footfall of the past. The vast majority of the footpaths showing on maps were really just local routes from house A to farm B. They don't really have a modern day purpose other than to bewilder this man of the North, where pathways are well marked and often wide. Of course should I reside here in Herefordshire I'd get to know the local patch and stride out like a giraffe on a mission. But I have to say, for the casual wanderer it can be exhausting having to think on one's feet.

Klvert presumably thought on his feet while walking, mentally composing sermons, taking in the views, or bucolically viewing the diamonds glistening on the Wye. Following in his footsteps made me think, though a privileged life in many ways, a Victorian country vicar's role was a hard one. Through necessity walking in all weathers to offer comfort to parishioners, the inclement weather of winter must have sucked all the energy out of the resident man of God, guiding his servant on earth through the pestilence and toil. I'd have liked to have met him.

Time for another log on the woodburner then.... bliss, the rain's stopped I see out the window...