The tree has been felled. What do I think?

Like millions around the world I was alerted to breaking news last Thursday at breakfast time. The iconic sycamore tree at Sycamore Gap on Hadrian's Wall had been felled. At that time mis-information suggested it had simply blown over during Storm Arwen. But even I, a man who'd not held a chainsaw in anger for 30 years, could see this felling was at the hands of a much lesser force, Mankind.

Like many I was angry, more angry than I could have possibly imagined. I was upset, it really troubled me that this had happened. Who could be so crass as to have done this to a beautiful landmark. My best friend was on holiday in southern Spain. He lives literally on top of Hadrian's Wall, it runs underneath the kitchen of his converted Chapel, only a stone's throw from Sycamore Gap. I texted him. His replied was immediate and simple "Eh????". Exactly my reaction on hearing this. I couldn't believe what I was reading.

Quite a bit of that reading was hilarious as journalists who had no idea about this tree sprang into action. One copy in the on-line edition of the Daily Mirror had the headline, "Beautiful 300 year old tree planted between 1840 and 1860 felled by vandals". Even with my mathematical incompetence I think they had the dates wrong. It was soon changed. The BBC Website ran a headline for a few minutes "Medieval tree visited by Robin Hood felled near Hadrian's Wall". Obviously that journalist's only fact gleaned from the press releases that speed around broadcast media's newsrooms was that Kevin Costner in the 1991 film Prince of Thieves travelled from Dover to Sycamore Gap on foot in one day. Some copy was even more bizarre. The New York Times initially ran with Sycamore Tree felled near Scotland. I read on, realising how isolated the American press is. Northumberland was mentioned in the third paragraph and apparently Hadrian's Wall is a short drive from Scotland's beautiful capital home of whisky and Robbie Burn's. Of course American's only know about Scotland, so in modern terms it was simply click bait.

But all this smoke and mirrors aside, there is a real sense of anger prevailing over this felling of a single tree. I completely understand this sentiment, for many the tree stood for something, whether that was personal, aesthetic, natural history, a symbol that represented the north east or simply a focal point for a lovely photograph. But why was I so angry? I'd never been there.

Northumberland is a beautiful county and littered across this landscape are magnificent sycamore trees such as those I photographed above near Matfen in mid Northumberland a few years ago. Every farmstead, field and village has mature sycamores as a permanent symbol living in and of the landscape. Most, like the one now lying on it's side, are 200-300 years old. They are majestic and I love them, as they remind me of being a child, lazy sunny summer days when I'd be out for a wander near Rothbury and often found myself resting with my back on the trunk of a sycamore while I drank my ginger beer or ate a massive gobstopper. However I'd never been to 'the' sycamore at Sycamore Gap, a name which is itself fairly modern, as it was allegedly just made up by a Lawrence Hewer when an Ordnance Survey team visited and wanted to know what the feature was called.

I'd driven past the Gap many times while on the 'Military Road', in the same way that many motorists on the A303 pass Stonehenge but don't stop but admire the view. I'd even stopped the car once when my Canadian cousins were visiting on their whistle stop tour of Britain so we could take a quick photo out of the car window. But although I've walked sections of Hadrian's Wall, I'd never got to the tree. And that is what interests me in two ways. Firstly it was a difficult place to reach even in daylight, so how on earth was a hefty chainsaw carried over there in complete darkness? It really is dark up there. But secondly, why did the loss of a tree I only knew of from a distance affect me?

I think answering that latter point is easy. As we age, loss becomes a larger part in our lives as our own mortality comes over the horizon, and trees themselves are meant to be permanent - we don't lose them - but if we do it matters.

Take the image below, the oak on the right of this hedge line is known as Julie's tree.

Nobody calls it Julie's tree apart from my wife, the very same Julie and myself. This was a landscape I got to know when we first met, the wide rolling landscapes that surrounded her village in Wiltshire. We walked up here on one of my first visits and while almost identical to every other tree for miles around this tree, (along with another in the village that was fenced off and we couldn't visit anymore), became "our" tree. And that is the answer. Permanence in the landscape grabs hold of the soul and never escapes. Julie moved to Somerset in 2014 and since then we've not been back to 'our' tree. I hope it still stands and hope it is well, but in my mind it is a permanent symbol of a happy time for both of us in Wiltshire.

The image of me at the top of this post is of Blindburn at the head of the Coquet Valley in Northumberland. I love it up here but have absolutely no connection to it other than it means something to me as a casual visitor. But I feel protective towards it. Oddly though, my wife owns a house further down the valley at Harbottle which we have no spiritual connection to. Julie may own it but it is occupied by a long term tenant and his family, a local family with children which is a wonderful addition for the village. But as we don't live there, that full blown spiritual connection will be focussed on those children growing up in this wonderful part of the world, not me. But I still have some connection.

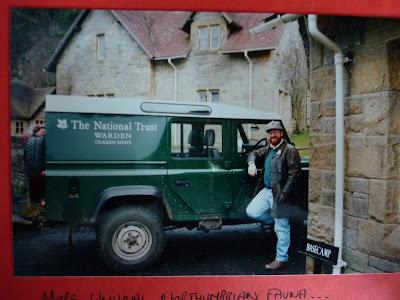

Academic careers have been made analysing what it is to have a memory, what it means to experience spirituality or a Spirit of Place, that historical record of a time and a place that means something in that precise moment of time to an individual when we are there, alive and living. In a similar vein the below image of me as a volunteer warden at the National Trust's property of Cragside in Northumberland in the 1980s is another example. I didn't perform paid work there, I never lived on the estate, but for about six years, I spent every weekend there doing something I absolutely loved, being out in nature, learning how wardens (now rangers) operate and meeting the public. I forged fantastic long term friendships there, but then I moved south and I've only returned a couple of times as a visitor. But if anything catastrophic happened to Cragside, as happened to the sycamore at Sycamore Gap, I'd be devastated.

The wanton destruction of the sycamore on Hadrian's Wall was an abominable act. Why someone thought it was a good idea to illegally fell a beautiful tree is not something I think anyone will find out soon. But it's gone. Many people are suggesting what happens next. An Anthony Gormley sculpture in its place. I personally hope this doesn't happen. A wooden sculpture of the tree made from the trunk. Maybe, but can this be in a museum or arts centre. I worry the site may become a bizarre shrine to something that was once loved but has gone, eradicated and will never ever come back. Nature carries on if we let it, but what replaces it will never be what was there.

There was an excellent comment by Gary Bartlett I read, who perfectly summarised my thoughts on what may happen to one option. The National Trust and many others are suggesting the coppicing of the stump will preserve the tree. I don't know Gary, but he writes......

" It's a nice thought.... But let's be realistic. I first met this particular tree in 1990 when surveying the trees on sections of Hadrians wall. This Sycamore was in it's unadulterated natural form, three centuries in the making. It had a twin stem which added to it's aesthetic appeal.

Sycamore will respond to hard pruning but a coppice or a pollard never take on the appearance of the natural form... You can go to Sherwood forest and see 700yr old oaks that haven't been pollarded for well over a hundred years... And they still bear the signatures of the woodman's saw. There is a reasonable possibility that this tree will soon throw multiple shoots up from the stump - it will have the appearance of a scruffy thicket for a few years. With careful selection of maybe 2 or 3 dominant stems (& their protection from further vandalism); a new tree may be crafted... After 10yrs of nurture, a new multi-stem tree with a natural habit may be visibly appreciated & in 40 to 50 years it may have the appearance of a reasonably mature tree. It will be 80+ years before it has anything like the stature of what was lost & another 50yrs beyond that until it has any sense of grandeur. In the meantime, the tree will be vulnerable to pathogens - especially fungal.

It is exposed to fairly strong winds - and sucker shoots in maple species are prone to tearing out at their union with the stump or stub. This structural weakness will be ever present for the first 20-30yrs at least. Sycamore don't tend to send up daughter plants / clones away from the stump like many Prunus or Poplus species will... So new shoots will be limited to the stump - which will in time decay from the centre... There is a risk that the shock of losing the main stem might kill the tree (at this age), so regeneration is not guaranteed.

Planting a replacement will be challenging as the site is a scheduled ancient monument - so a planting site would need to be identified for a new tree - agreed by Historic England / English Heritage and the National Trust (whichever have jurisdiction on this section of Hadrian's wall). An archaeological dig would likely be required before a new tree could be planted.

The tree that has been lost will never be replicated - it was unique.

Northumberland has many tens of thousands of Sycamore trees; many of which are older, taller, broader and arguably more magnificent than this one (I urge you to seek them out - they will warm your soul).

But this tree was the iconic "Sycamore Gap" tree... It cannot be replaced by a tribute act.

This tree seems to have become a metaphor for man's relationship with all trees... From the Amazonian rain forests, to trees being felled for access to building sites or new infrastructure. It's loss feels like the assassination of Martin Luther King or Kennedy... Senseless."

Gary Bartlett ended his piece with these words on the desire to coppice.

[I admire the optimism.... ]... Unfortunately few of us will be around to discuss this by the time this tree may become anything reminiscent of the original."

Other people will have many other views and that is how it should be. But for me now some forty eight hours into the story, this is how I'm increasingly feeling. The anger I felt at that tree's destruction has softened. I'll now never visit the tree, but, and this is important, if it had been such an important part of my life, I'd have made the effort to visit it while it still stood. Now, my mind is focused on change and the future. Let the fallen tree decay at it's own rate into the landscape, help dead wood invertebrates and plants thrive for a few decades in this most treeless of landscapes. Plant something new, maybe not in the same place, but nearby. The loss felt by my generation by this criminal act could benefit generations to come. I remember visiting Kew Gardens while on a botanical course in February 1988, just months after the October 1987 storm had ripped through the gardens. Many much loved trees from their specimen area had fallen. It was while on a walk around the site, then still closed off to the public, with Kew's arboriculturalist that he said something I've never forgotten.

"[sic] Arriving at Kew on the morning after the storm he cried and cried for the lost trees there, many of whom he thought of as family. But then as the weeks passed he realised this was a moment to embrace change and plan for the future."

Looking at Kew Gardens now it's almost impossible to imagine the damage caused on that October night. My hope then is the same fate befalls the toppling of this sycamore. Over the months and years we'll see change at Sycamore Gap. We as a society must and can look forward. What can we do as a society to make the landscape better for children being born in 200 years time? We have benefited from a tree being planted in the 18th Century maturing in the age of Social Media. Much like the trees below in the field next to the aforementioned friend's house only a stone's throw from Sycamore Gap which I photographed while on a walk before breakfast last November. They're just trees, no one except the odd walker will notice them. They stand there quietly removed from the consciousness of collective society. Would anyone miss these unknown trees if they were felled one night? I doubt it, and that is a most sobering thought.